My husband has been playing ice hockey since he was four years old. Even when we moved to the South, where the dominant sports were NCAA hoops and Nascar, it didn’t deter his enthusiasm or his love of the game. He started pickup games, and with the inevitable migration of other Northerners to the area, ice-hockey pickup games turned into teams and then into full-fledged leagues. Back then, Canadian beer companies were looking to break into the southeast region, and my husband’s chance encounter with a marketing rep led to a sponsorship by LaBatt™ Brewing Company. As captain, my husband landed free team jerseys, the team name “LaBatt Blues” and two cases of beer a week; not a bad score from a chance encounter at a local Raleigh grocery chain.

But many things have changed for professional hockey. We now have a NHL team in the Carolinas, and the majority of NHL hockey players use hockey sticks made of composite materials. Twenty-five, even thirty years ago the hockey stick of choice for every NHL player was one of all-wood construction. However, by the 1980s wooden hockey sticks gave way to aluminum shafts with wooden blade construction to today’s one piece sticks made of fiberglass, Kevlar or graphite composites, leaving only a handful of NHL hockey players using wooden hockey sticks in the professional league.

According to a few reports, including some in the Denver Post, a few NHL players have been holding on to the tradition of wooden hockey sticks, the smell of scorched wood and glue from molding their blades to the shaft of their sticks permeating the locker room before a game. Prevailing perceptions have many believing that composite hockey sticks are lighter, and therefore heightens the speed of the puck for repeated goals. But many stats and even professional hockey players themselves who use wooden hockey sticks suggest otherwise. Just ask Adrian Aucoin, defenseman for the Phoenix Coyotes, who won the 2007 NHL team skills competition with a slapshot of 102.3 mph using a $30 wooden stick, or Fredrik Modin, one of the few NHL players to win a Stanley Cup, a World Championship and an Olympic Gold medal using wooden hockey sticks as his preference. The theory that the more expensive hockey sticks make you a better player just doesn’t stick anymore.

What is “Tradition” is Suddenly “New” Again

Certain hockey traditions refuse to die, and so it is for a little town in Roseau, Minnesota, with a population of 2,613. This is the tiny town where huge hockey legends are born and leave to win Olympic gold, world championships and Stanley Cups. Home to Polaris Industries, a maker of snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles, it can now boast home to another industry: wooden hockey sticks. BOA Athletics, a Denver-based company, has recently purchased the Roseau factory that made the Christian Brother Hockey sticks a household name for countless Minnesota kids who grew up on ice hockey. Under the moniker “Nice Guys, Tough Sticks”, generations of the Christian family grew up playing hockey, bringing their father’s love of carpentry and their love of the game into a union that ultimately saw wooden hockey stick manufacturing cease in part to increased competition from larger retailers and a consumer shift towards composite sticks.

However, things change, and so did the upper management of BOA, who saw ingenuity and renewed integrity in puck handling using wooden hockey sticks. Not to mention the fact that each wooden hockey stick, because of its soft wood properties, can be designed according to a hockey player’s desired specifications. Because of the high cost and breakage of composite hockey sticks, some priced at $300, BOA of Denver is betting that a return to wooden hockey sticks will work in their favor. With the illustrious title of the “only manufacturer of wooden hockey sticks in the USA”, BOA hopes their customized three-pack of BOA sticks, which starts at $135, brings more competition to the playing field.

The Science behind “He Shoots He Scores”

A lot of engineering is behind the making of wooden hockey sticks, and each one is an exact replica of a hockey stick used by NHL professional hockey players. To begin the process, workers take a piece of poplar wood with a moisture content (MC) between 9-15% and glue two thin strips of birch to it. It is then placed on a circular conveyor equipped with a press, which holds the pieces together while the glue dries. A multi-bladed saw cuts the wood into three identical stick shaft pieces. The shafts are then moved to a precision sander. Once sanded, workers apply an epoxy resin, a carbon-reinforced fiberglass coating, with a roller. To dry the resin, the stick shaft is placed in an individual mold cooked in a press to 80 degrees for 12 minutes. The shaft then goes to a milling machine with diamond-headed knives that round the edges the entire length of the stick shaft. A finish is applied to the stick shaft and then it goes in for a second sanding to bring out the grain of the wood. Workers glue small blocks at the end of the shaft to attach the blade, and then apply urethane glue to the stick so that it resists moisture and humidity. This urethane dries for 15 minutes at 100 degrees.

Once dried, the stick shaft is carried to the slitter, where the wood blocks are cut to slide into the blade. Once the blade is in place, a computer-controlled lathe cuts the blade to precision. The sanded blade needs to be curved, so it is placed in a blade mold and steamed for 50 seconds at 131 degrees, allowing humidity to penetrate the blade to make it flexible. The blade is then worked by hand, where it is compared to standardized blade patterns for optimal curvature. At one time, the Sherwood plant in Montreal had over 6000 blade patterns on hand. In professional hockey, blade curvature is kept to ¾ inches, and using a blade with an illegal curve is punishable with a two minute minor penalty. Back at the factory, the blade is sanded to the desired thickness and reinforced by using a fiberglass cloth soaked with epoxy resin, which is placed on the blade leaving a good margin of excess while getting rid of air bubbles and then oven dried at 90 degrees for 24 hours. The surplus fiberglass is cut away manually. Finishing is done with a circular sander, and finally the blade is dipped to give it a nice luster. Once the sheen has completely dried, silk screeners apply the logos.

Tradition is no stranger to Wagner Meters. Since the 1960s, Wagner Meters has built on one solid dream of its founding owner, Delmer Wagner, of providing better moisture measurement technology to the wood products industry in the pursuit of consistent, accurate MC testing. Delmer Wagner developed the first non-contact in-line lumber moisture detector, which soon drew requests for product development of the compact hand-held moisture meter technology for wood and concrete used today by contractors, manufacturers, building inspectors and hobbyists around the world. Some of the best things in life are steeped in tradition, and Wagner Meters is proud to be a part of that great American tradition.

And admittedly…I’m proud to be a part of their team.

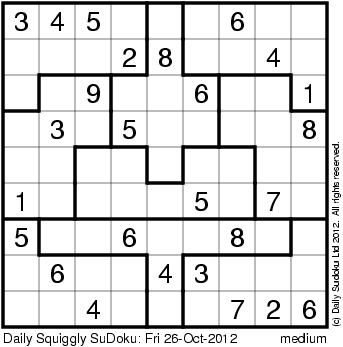

Crafty Puzzles